Captions & photographs © by Guillaume Bonn for Paradise Inc.

Conservation efforts—including moving black rhinos to Borana, Lewa, and Nakuru—have helped double populations in protected areas. But growing human encroachment and shrinking wilderness mean these strategies may only serve as stopgaps unless conservation approaches evolve.

The wilderness is shrinking into fragmented enclaves of farms, towns, and roads. A railway slicing through Nairobi National Park, zebras grazing beneath it, captures the urgent question: can human progress coexist with wildlife survival?

On Sundays, families gather on a beach outside the city—a scene of calm that contrasts with projections for 2050, when Africa’s population will reach 25% of the world’s total, driving resource demands and straining already fragile habitats and wildlife.

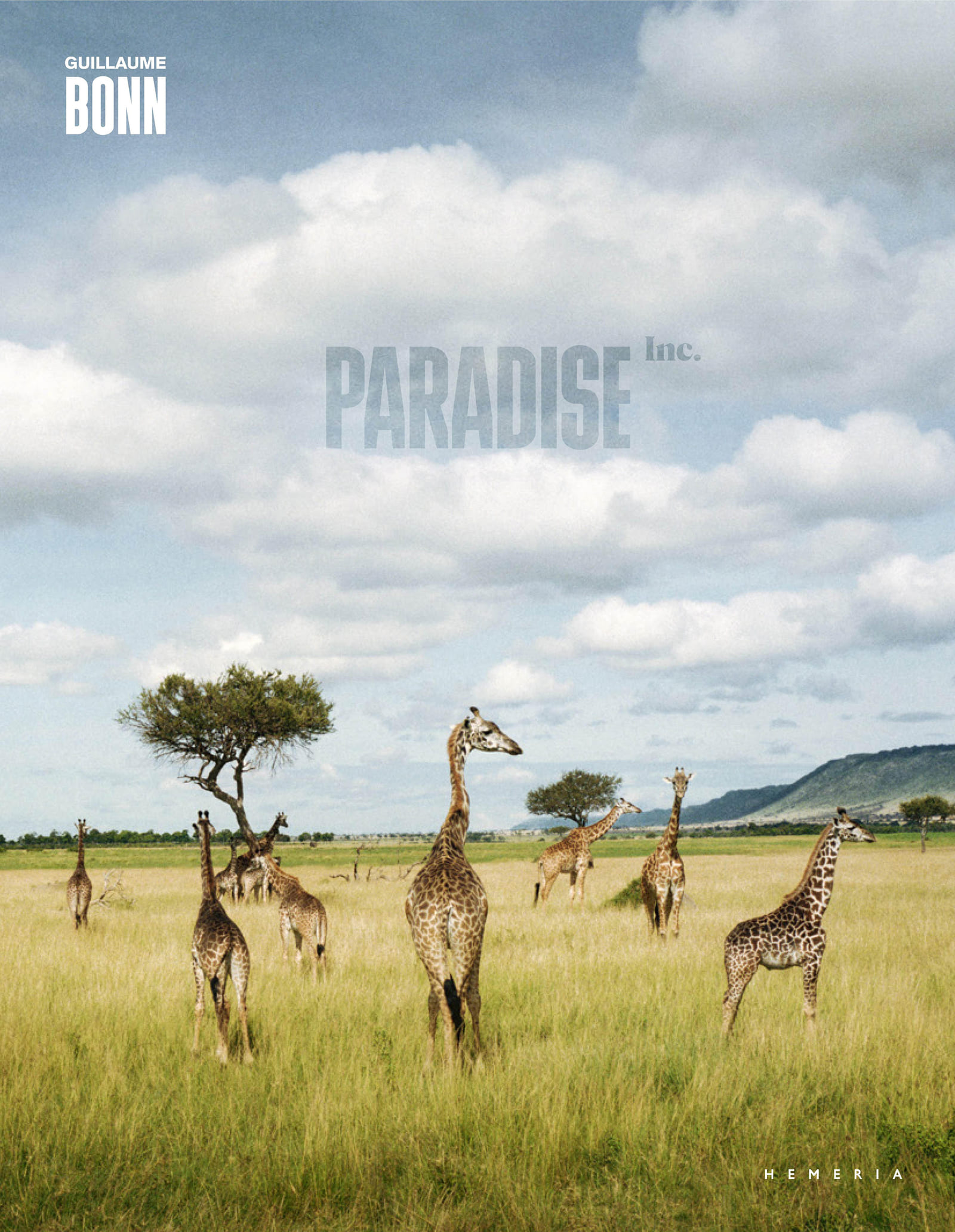

The Masai Mara Reserve, in southwestern Kenya, which alone is home to 25% of the country’s wildlife, faces alarming over-tourism, posing a significant threat to the fragile balance of its ecosystem.

The Masai Mara, Kenya’s premier safari destination, is famed for its rich wildlife—but massive hotel development and over-tourism now threaten the fragile ecosystem that holds a quarter of the country’s animals.

A new high-rise in Mombasa, soon to become private apartments, illustrates Africa’s rapid urbanization—a trend that, with the continent’s population projected to reach 25% of the world’s total by 2050, will intensify pressure on shrinking wilderness and the wildlife that depend on it.

Not long ago, this hut lacked windows or a locked door. Traditional life relied on community, shared resources, and collective trust—but the arrival of Western capitalist ideals, focused on profit, began to change that balance.

Turkana is an arid, economically disadvantaged, and isolated region that has long been neglected by successive administrations. It is a place where pastoralist communities continue to adhere to traditional ways of life.

Turkana, an arid and long-neglected region, is home to pastoralist communities maintaining traditional ways of life—yet recent oil discoveries and developments, like this new gas station, signal the arrival of modern progress.

Just outside a main entrance to the Masai Mara lies an unmonitored settlement. Interestingly, most wildlife—83.7% according to WWF 2021—lives outside the protected reserve, with only 16.2% found within its boundaries.

A woman chops a tree on the outskirts of the Maasai Mara, using it for charcoal or warmth. Human settlement around the reserve has devastated wildlife—WWF studies show losses of up to 95% for giraffes, 80% for warthogs, 76% for hartebeests, and 67% for impalas—while also stripping the vegetation that non-predatory animals rely on for food.

Each year, over a million wildebeest migrate from Tanzania’s Serengeti into Kenya’s Maasai Mara—a breathtaking spectacle. Yet the reserve is under threat: over-tourism, unchecked development, and hotel expansion are straining the ecosystem that hosts 25% of Kenya’s wildlife, with corruption and weak governance leaving it unprotected.

Illegally dumped garbage sits just an hour from Lodwar in Kenya’s Turkana region. While developing countries call for compensation for climate change, they often overlook the degradation of their own habitats, ecosystems, and local environment

A warthog forages through the trash of a luxury eco-lodge on the edge of the Masai Mara. The reserve’s ecosystem is heavily strained by unchecked—and often illegal—hotel developments, enabled by widespread corruption.

In East Africa, truly wild safari experiences are becoming rare, as population growth and poverty shrink natural habitats. Rising tourism demand and local corruption have fueled excessive hotel construction, putting even more pressure on wildlife that still roams freely—for now.

A chef at a nearby lodge prepares breakfast for guests returning from an early hot air balloon ride, while the Masai Mara faces ecological strain. Heavy hotel investments, over-tourism, and local population pressures are squeezing the reserve, where humans and wildlife increasingly compete for space and resources.

A quarry beyond the Masai Mara Reserve supplies materials for new lodges, cutting into traditional grazing and hunting areas for wildlife. As the reserve can no longer support all its animals, human-wildlife conflicts are on the rise.

A rhino is sedated for transport to avoid deadly territorial fights as its habitat shrinks. Dehorning offers only partial protection—rhinos are still killed, and without real political action, long-term survival remains at risk.

A young eland near Ololoo Gate, Mara Triangle. WWF studies (1989–2003) show dramatic declines in ungulates—up to 95% for giraffes—largely due to expanding human settlements around the reserve.